My first summer internship with the Mugello Valley Archaeological Project (MVAP) at Poggio Colla has wrapped up, and it was an incredible season with exceptional finds! Under the guidance of head conservator, Allison Lewis—a UCLA/Getty alum (‘08 )—and with the sponsorship of The Etruscan Foundation’s 2014 Conservation Fellowship, I was afforded the amazing opportunity to participate in this project, which has been underway for the last several decades. MVAP has significantly contributed to the study of ancient Etruria with their work at Poggio Colla, the site of a hilltop settlement and sanctuary that spanned the 7th-2nd centuries B.C.E.

A particularly groundbreaking find happened in 2011, when a student participating in the MVAP field school found a stamped bucchero fragment that appears to depict a woman in the midst of childbirth. This imagery is the earliest documented in Italy and nearly unparalleled in the ancient Mediterranean, however study of the finely recessed scene is difficult due to its small size and worn nature. It takes just the right angle of raking light to highlight the surfaces and make the scene legible (Fig. 1), which is often the case with these stamped and incised bucchero vessel fragments.

![Fig.1. The birthing stamp (inv. PC 11-003), found on a bucchero fragment, measures just around a centimeter in height and is worn, requiring magnification and raking light to study its imagery. [Photos courtesy of Dr. Phil Perkins, The Open University].](https://uclagettyprogram.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/blog_fig_1.jpg?w=820&h=500)

Fig.1. The birthing stamp (inv. PC 11-003), found on a bucchero fragment, measures just around a centimeter in height and is worn, requiring magnification and raking light to study its imagery. [Photos courtesy of Dr. Phil Perkins, The Open University].

As an 2014 Etruscan Foundation Conservation Fellow, I proposed a special project to the Foundation involving the documentation of bucchero fragments using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), which Allison has wanted to test at Poggio Colla for several field seasons. This technique, created by Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI), involves a low-cost, easy photographic set-up that can be macgyvered in the field with fairly basic supplies (Fig. 2). RTI essentially blends a series of photos of an object under different angles of light to create an interactive file (a polynomial texture map) that one then explores using a “virtual torch” in various rendering modes. In other words, instead of researchers straining their eyes and handling the object in different raking light or studying static images, they can explore the features and subtle details of the object’s surface in a single, high-resolution image with an adjustable light source that they can control.

Fig. 2. We were able to disassemble a standard desk lamp to become our movable light source, much to our excitement! This imaging technique was affectionately called “A Thousand Points of Light” amongst the staff, and it was pointed out that it’s quite a ritualistic process (appropriate for the sanctuary site) as we huddle on the floor around an ancient artifact with a single torch lighting us.

Our set-up was simple. We picked a relatively closed-off room adjacent to the field conservation lab where we could have good control over ambient light; as you can see, it doesn’t have to be a special room-nor a room at all if you’re on-site! We used the lab’s point-and-shoot Canon G10 digital camera with a remote so as not to shake the camera when capturing the images, a copy stand, a disassembled desk lamp that we tethered to a string, and small, black reflectance spheres purchased by the conservator prior to the season (Fig. 2).

The black spheres are required in the frame near the object, in order to reflect the location of the light source for the software during image processing (Fig. 3). Any black, reflective sphere can be used; Allison purchased 1/4” and 7/16” silicon nitride (Si3N4) ceramic balls used for ball bearings (Boca Bearing Company), which we mounted in frame with Benchmark wax, at times stuck to bamboo skewers to be held level with the object’s surface. The string tied to the lamp was measured to roughly 4x the diameter of our object, becoming the fixed radius at which we moved the light around the object for each photo (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3. Items inserted in frame for image processing or posterity (such as the black spheres, grey scales, or labels) can be cropped out in the final stage of processing in RTIBuilder so that your final product is simply your subject, to be navigated and explored in RTIViewer.

Keeping the camera in a stationary position with our object and black spheres in focus, we proceeded to take around eighty images per object, with each object taking roughly fifteen minutes to shoot; one person snapped the photo while the other moved the light. We continued taking photos until we felt we covered a full “umbrella” of light around the object in our series of images.

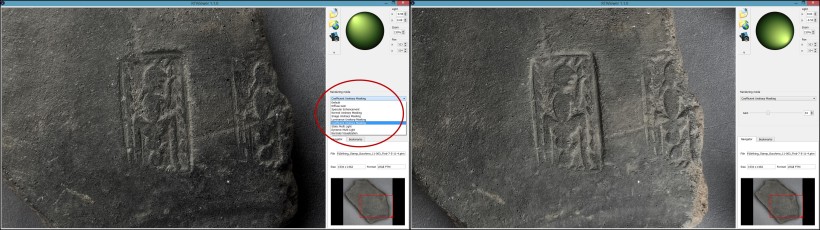

The photos were then processed using the RTI software (RTIBuilder), which is available for free on CHI’s website, along with RTIViewer for navigating the final product. RTIBuilder can be finicky and particular, especially in naming files. No spaces, hashtags or other similar characters are acceptable in file names. We also found that the program did not recognize capitalized file extensions (for example not .JPEG files, only .jpeg) so if you can’t control which file type you’re capturing in on your camera, you’ll need a computer with Photoshop or an equivalent image processing software that can convert them. For optimal quality, CHI recommends capturing images in RAW and then converting to jpegs (RTIBuilder can only process jpeg files). Processing items inserted in frame (black spheres, gray scale, label, etc.) can be cropped out at the end before the images are converted into the single digital file, which can be interactively viewed by anyone who has downloaded the free RTIViewer (Figs. 3-5).

Fig. 4. When you open RTIViewer, you have several options at your disposal: you can control your light source; you can zoom in and out on your subject and move around over its surface; you can take a snapshot of your field of view (which saves as a .jpg and XMP file); and you can play with a diverse range of rendering modes available in the dropdown menu.

Fig. 5. The different rendering modes can emphasize or deemphasize particular surface characteristics, and some modes allow you to study the surface without the distraction of surface pigment/colors.

As you can see, this imaging technique offers a different, versatile way of studying the morphological and topographic features of an object’s surface, no matter how minute, without the need to access the object itself. Given the various rendering modes available in the RTIViewer, it can be used as a supplementary tool in examining the object, and it can also be offered as an alternative format for researchers wanting to study the piece, limiting unnecessary handling….which we conservators like to hear! We found RTI to be an especially useful field tool for recording and studying worn, stamped bucchero decoration, fabrication related marks on bucchero surfaces, and incised characters on ceramic and stone surfaces (Figs. 6-8). After a great pilot program, the MVAP conservation staff and other project members hope to continue exploring its potential applications at Poggio Colla in future seasons.

Fig. 7. A bucchero sherd (inv. PC 14-062) with reticulate burnishing, nearly invisible under even light (note the ‘Default’ image). Modes like ‘Normal Unsharp Masking’ can reveal the very subtle, recessed burnishing marks, and others like ‘Diffuse Gain’ can contrast them.

Heather White (’16)

Pingback: 43rd Annual Meeting – Textiles Specialty Group, May 14th, “Lights, Camera, Archaeology: Documenting Archaeological Textile Impressions with Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI)” by Emily Frank | Conservators Converse

February 9, 2018 at 8:53 am

Excellent article thank you